This article is written for solo female travelers visiting Japan as part of our women-only tour or on their own.

You will find a brief history of the country, tips for the best time to visit, travel essentials and entry requirements, health and safety advice, and some local culture, from basic Japanese etiquette, to some easy vocab, and the best foods and drinks to try.

I have also included a reading list, and a few movies and shows to watch to immerse yourself in the culture.

Looking for what to pack? You can find our Japan packing list here.

さあ行こう (Let’s go!)

Intro to the history of Japan

Japan is an archipelago of 14,125 islands, strung together like a ribbon between the Sea of Japan and the Pacific Ocean. It’s close enough to mainland Asia to be influenced by it, but far enough from it to never fully blend in.

The earliest people in Japan were hunter-gatherer communities who formed small settlements during the Jōmon era, more than 14,000 years ago. These early inhabitants lived closely with the land long before emperors, castles, or samurai, and left behind pottery unlike anything else found in East Asia (the name Jōmon means “cord-patterned pottery”).

During the following Yayoi period (c. 300 BC – 300 AD), rice farming arrived from the Asian mainland. Villages became more permanent, populations grew, and social structures took shape. Food, rituals, and seasonal rhythms began to influence daily life in ways that still feel familiar today, even though they are thousands of years old.

Japan’s long story is often told through its Emperors and ruling families. The imperial line itself is considered the oldest continuous hereditary monarchy in the world, traditionally traced back to Emperor Jimmu, the semi-mythical first ruler.

By the 3rd to 6th centuries, powerful clans, especially the Yamato clan, were asserting control in central Japan, and an imperial state began to form.

In 710, Japan established its first permanent capital in Nara, and over the centuries that followed, the country developed a distinctly Japanese culture. Indigenous Shinto beliefs, rooted in nature and ancestor worship, blended with Buddhism, which arrived from the mainland in the 6th century.

Religion didn’t arrive as a replacement, but as an addition. Instead of choosing one over the other, Japan kept both. This habit of layering rather than erasing became a defining pattern: old stays, new arrives, and somehow they coexist.

The Heian period (794–1185) is widely regarded as a high point of classical Japanese culture (Heian (平安) means ‘peace’ in Japanese). Court life flourished, literature and poetry thrived, and Chinese influence declined allowing a national culture to form.

From the late 12th century onward, power shifted away from the Imperial Court to military rule, beginning when Minamoto no Yoritomo established the first shogunate in Kamakura in 1192. For centuries after, regional warlords, samurai codes, and feudal loyalty would shape Japan’s daily life.

During this time, Emperors became symbolic figures, while real political power was held by military governments led by shoguns. The “shogun” served as Japan’s supreme military and political authority, effectively ruling the country while the Emperor remained its spiritual and ceremonial head.

Samurai culture evolved not just as a fighting class, but as a way of thinking, emphasising loyalty, discipline, and personal responsibility, and this shaped many values still seen in honor and etiquette today (see our section below on Japanese cultural etiquette).

Japan experienced prolonged periods of internal conflict before eventual unification under leaders such as Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and finally Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The Edo (Tokugawa) shogunate was Japan’s last feudal military government. From 1603 to 1868 it saw 265 years of peace and stability, during which Japan closed its borders and deeply restricted foreign contact.

In 1868, the Meiji Restoration marked a dramatic return of power to the emperor under Emperor Meiji and a deliberate opening to the outside world. Western ideas flowed in rapidly, and the country modernised almost overnight.

Railways, factories, modern education, and new political institutions appeared within decades. It was fast, messy, and intentional. Shrines and smokestacks began rising side by side.

The 20th century brought devastation, recovery, and reinvention, with World War II marking the most destructive period in Japanese history.

Tokyo, Osaka, and dozens of other cities were heavily firebombed, destroying large areas of urban Japan and causing immense civilian loss of life. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 brought sudden, unimaginable suffering and long-term consequences that are still felt today.

When the war ended, Japan faced food shortages, shattered infrastructure, and a deeply shaken sense of identity. What followed was one of the most deliberate rebuilds in modern history.

Under postwar occupation, Japan rewrote its Constitution, introduced democratic reforms, and invested heavily in education, industry, and public life. The speed and care of this reconstruction laid the foundations for the country’s long-term stability.

By the 1950s and 1960s, Japan entered an economic boom, with manufacturing, technology, and exports transforming the country. The late 20th century saw Japan emerge as a global leader in cars, electronics, design, and innovation, even amid economic bubbles and slowdowns.

In recent decades, Japan has focused on balancing tradition with change; adapting traditions rather than allowing them to disappear, and this balance is what we notice most today. You’ll see it when a centuries-old shrine sits quietly behind a convenience store, or when a high-speed train glides past rice fields that haven’t changed in generations.

Interesting facts about Japan

Japan is a unique country that is hard to compare to anywhere else in the world so there are a lot of unique and interesting things that will catch your attention during a visit.

Below are some fun and interesting facts:

- Japan is an archipelago of 14,125 islands after the 2023 survey. Japan isn’t just one island, it’s thousands. Most visitors stick to the four main islands, but the smaller ones shape everything from food culture to weather patterns. It’s why Japan feels coastal even when you’re inland.

The four main islands are Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku. Honshu holds Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka. Hokkaido runs cooler, and has all the famous ski resorts. Kyushu feels warmer and volcanic. Shikoku is quieter and more rural. Each one has its own personality.

- Japan runs on Japan Standard Time (UTC +9). There’s no daylight savings here. Time stays steady year-round, which locals appreciate. DST was used from 1948 to 1952 under American occupation, but abandoned after the occupation ended.

- The population of Japan is around 124 million people making it one of the largest countries in the world in terms of population. That density explains the efficiency. Trains run on time because they have to. Space is respected because it’s shared.

The country’s capital, Tokyo, is one of the largest cities on Earth with between 37 and 40 million people in its Greater Tokyo Area. Tokyo isn’t just big, it’s layered. Tiny bars under train tracks. Peaceful shrines beside office towers. It works because it’s organised chaos.

- The Japanese eat KFC on Christmas day. The folks at KFC can pat themselves on the back for creating a quirky tradition that has now been held for years and is the result of great marketing, timing, and cultural context. In 1974, KFC Japan launched a campaign called 「クリスマスにはケンタッキー」 (“Kentucky for Christmas”) that promoted their chicken as a Western-style substitute for the hard to find roast turkey. Christmas isn’t a holiday in Japan, as Christians only represent 1% of the population, but it is seen as a romantic celebration like Valentine’s Day and KFC managed to position its food as a modern take on the holiday. Locals will pre-order their Christmas day feast well in advance and on Christmas day, and long lines are seen outside stores to collect it.

- Public transport is famously reliable. Trains are fast, clean, and precise. Delays are rare (on average 18 seconds) and apologies are sincere. The Shinkansen (bullet train) connects the country, and these trains are fast, smooth, and make long distances surprisingly easy.

- Japan is home to many innovations. Capsule hotels, robot hotels and restaurants, interesting food flavors like sakura KitKat, manga and anime comicbooks, QR codes, instant ramen, and the high speed train among many other are all Japanese inventions.

- Cherry blossom season is a national event. When sakura blooms, the country pauses. Parks fill, cameras click, and timing becomes a national obsession. Our March / April tours take in the Sakura season.

- There are over 4 million vending machines in the country, and you can buy everything. They sell drinks, meals, and oddities, and you’ll find them on quiet residential streets, outside temples, and even in rural areas. Think hot coffee, cold tea, ice cream, snacks, umbrellas, batteries, and sometimes full meals. You can also buy souvenirs like socks that have become all the rage.

- Japan is one of the safest countries in the world. Violent crime is exceedingly rare. Solo travelers often comment on how secure they feel walking at night.

- Buddhism and Shintoism are the two main religions. They both have temples and shrines found all across the country, and both are very familiar to most Japanese people. Buddhism arrived in Japan in the mid-6th century (traditionally 552 or 538 CE). It came via Korea (Baekje), with roots in India, transmitted through China. By the Heian Period (794–1185), Buddhism was already well established and evolving into distinct Japanese schools (e.g. Tendai, Shingon). Shintoism on the other hand originated in ancient Japan, and follows the belief that there are thousands of kami (Gods) across the world found in nature.

Whilst many Japanese wouldn’t say they are strictly religious, many will perform religious practices from both Buddhism and Shintoism in daily life, such as visiting famous temples and shrines and offering a prayer, or participating in religious festivals known as “matsuri”.

Buying amulets at Japan’s most important temple

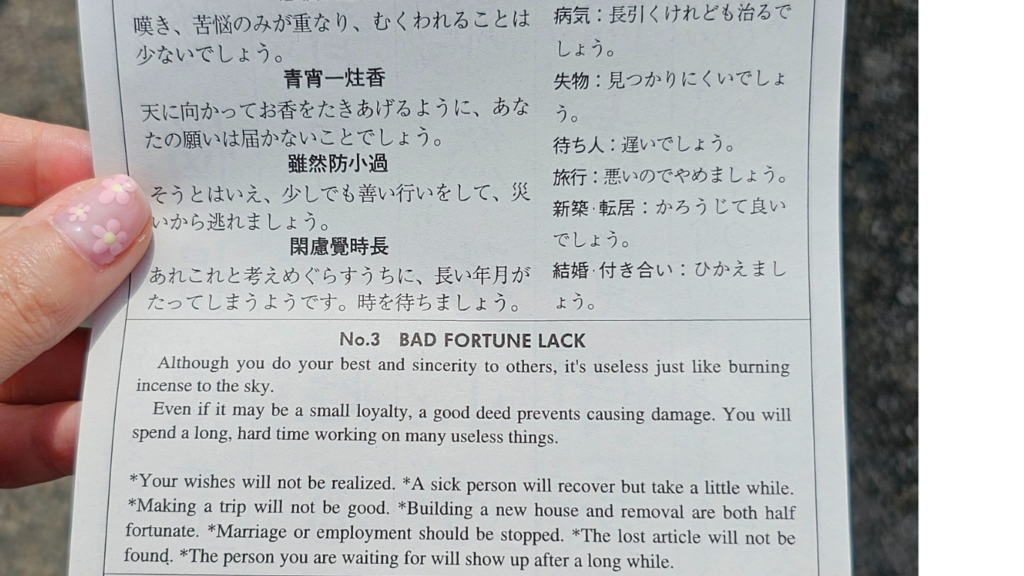

- The Japanese are very superstitious. Temples will have “Luck draws” where you can pull a message and read your luck. But beware, many will return bad luck! Amulets are for sale at most temples and you can also buy blessings by the monks. Number 4 is avoided on lifts, trains and floors because it sounds like “death” (shi).

- Japan sits on the Pacific Ring of Fire. Earthquakes happen, but buildings are designed for them and systems are impressively prepared.

- Sumo is Japan’s oldest national sport but baseball is the most popular. Football or basketball aren’t as popular in Japan as baseball is and players are real celebrities.

- Convenience stores are cultural institutions. 7-Elevens, FamilyMart, and Lawson sell good food, and run ATMs for international travelers. You will find entire meals there and pretty much anything you can think of. Most stay open all day and night.

- The Japanese monarchy is the oldest continuous hereditary monarchy in the world. The current Japanese Emperor is the direct descendent of Emperor Jimmu who came to power in 711 BC.

Japan travel tips

In this section, we will discuss various travel tips that will come in handy during a visit to Japan.

The Best Time to Visit Japan (+ Seasonal Festivals)

Japan has four clear seasons, and each one changes how the country feels – what people eat, how they dress, and how they celebrate.

Many of Japan’s most loved festivals are tied directly to these seasonal shifts, marking everything from the arrival of summer heat to harvest time or the changing of the leaves.

Japan hosts over 200,000 festivals (matsuri) each year, but below we’ve listed the major ones by season. To find festivals while you’re there, check city tourism websites (Kyoto, Osaka, Tokyo, etc.) for exact dates each year, ask hotel staff (they usually know what’s happening locally), look for posters near train stations and shrines, or simply Google the city name + “matsuri” once you’re in Japan.

Spring (March to May)

Spring in Japan is Cherry blossom season, and they usually begin blooming in late March, sweeping north over several weeks.

Cherry blossom timing shifts every year based on weather, so it’s worth tracking rather than guessing. The Japan Meteorological Corporation (JMC) releases official sakura forecasts starting in late winter, showing predicted bloom dates city by city as the blossoms move north. These are updated regularly and are easy to follow online or via weather apps.

Temperatures are mild and comfortable, but this is Japan’s peak season. Accommodation books quickly, trains are busy, and famous blossom spots can feel extremely crowded. The best spring festivals include:

- Matsuri (Cherry Blossom Viewing) – Late March to early April, and also known as Hanami (though Hanami is not specifically the festival, but more of a seasonal custom). Celebrated nationwide wherever cherry trees bloom. Picnics, parks, and quiet moments under falling petals.

- Takayama Spring Festival (Gifu) – Mid-April. Ornate floats, traditional music, and beautifully preserved streets. One of Japan’s most elegant festivals.

- Sanja Matsuri (Tokyo, Asakusa) – May. Rowdy, energetic, and loud in the best way. Portable shrines are carried through the streets near Senso-ji Temple.

Summer (June to August)

Summer arrives hot and humid, and it doesn’t pretend otherwise. June brings a rainy season, though rain usually comes in short bursts rather than all-day downpours. By July and August, the heat settles in, sticky, intense, unmistakable.

But this is also festival season. Streets fill with lanterns, fireworks light up rivers, and locals dress in lightweight yukata for evening celebrations. If you’re prepared for the heat and plan breaks indoors, summer offers some of the best festivals of the year.

- Gion Matsuri – Kyoto (July): Japan’s most famous festival, running all month with its peak parades in mid-July. Expect massive wooden floats, lantern-lit streets, and locals in summer kimono. If you’re in Kyoto in July, you’ll feel it everywhere.

- Tenjin Matsuri – Osaka (late July): One of Japan’s top three festivals. It mixes land parades with boats on the river, ending with fireworks over the water. Loud, lively, and very Osaka.

- Awa Odori – Tokushima (mid-August): A joyful dance festival where thousands of performers move through the streets in coordinated steps. Visitors are welcome to join in, even if you don’t know the moves (no one expects perfection).

- Nebuta Matsuri – Aomori (early August): Known for its enormous illuminated floats depicting warriors and folklore figures. It’s visually spectacular and feels completely different from festivals in central Japan.

- Kanto Matsuri – Akita (early August): Performers balance towering poles of lanterns on their hands, shoulders, and foreheads. It’s quieter than some festivals but incredibly impressive to watch.

- Sumida River Fireworks – Tokyo (late July): One of Tokyo’s biggest fireworks displays. Locals stake out riverbank spots hours in advance, and the atmosphere feels more like a picnic than a show.

Autumn (September to November)

Autumn is often the quiet favourite. The air cools and the landscape turns warm shades of red, orange, and gold. Autumn leaves (momiji) rival cherry blossoms for beauty, but feel calmer and less rushed, even though it’s a period that is quickly becoming as popular. It’s a wonderful time for temples, gardens, and scenic train rides.

Food becomes heartier too, with seasonal mushrooms, chestnuts, and comforting dishes appearing everywhere. Many travelers find autumn the most balanced time to visit; visually stunning without the intensity of peak spring.

Autumn festivals to travel for include:

- Takayama Autumn Festival (Gifu) – October. Considered one of Japan’s most beautiful festivals, especially in the evening when floats are illuminated.

- Jidai Matsuri (Kyoto) – 22 October. A historical parade that walks through Kyoto’s past, era by era, in full costume.

- Autumn Leaf Festivals (Nationwide) – October to November. Celebrations around fall foliage at temples, gardens, and mountain towns.

Winter (December to February)

Winter in Japan is crisp rather than harsh, especially in cities like Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka. Northern regions and mountain areas see heavy snow, making this prime season for snow festivals and hot spring escapes.

Cities feel calmer, streets are less crowded, and there’s something deeply comforting about warming up with ramen or soaking in an onsen while snow falls outside. If you enjoy quieter travel and don’t mind bundling up, winter shows Japan at its most serene.

- Sapporo Snow Festival (Hokkaido) – Early February. Massive snow and ice sculptures take over the city, drawing visitors from all over the world. Cold, yes – but unforgettable.

- Yokote Kamakura Festival (Akita) – February. Famous for its illuminated snow huts and winter rituals around shrines and temples.

Best time to visit Japan at a glance

- Best for cherry blossoms: Late March to early April (timing varies by region)

Best for comfortable weather: April–May and October–November - Best for festivals and summer energy: July and August

- Best for autumn colours: Late October to November

Best for fewer crowds: January–February and early December - Best for snow and hot springs: December to February

- Best for food lovers: Autumn, when seasonal ingredients shine

- Best overall balance: Autumn — beautiful scenery, calmer pace, and mild weather

Important Holidays in Japan

Travel during public holidays isn’t a problem, as Japan runs well even when busy. But crowds and prices increase around New Year, Golden Week, and Obon. If your visit overlaps these dates, booking trains and accommodation early makes all the difference.

New Year’s Day (Shōgatsu) – 1 January. This is the most important holiday of the year. Many businesses close for several days, temples and shrines are packed, and domestic travel spikes as people return home. Expect limited restaurant options early in the month and very busy trains.

Coming of Age Day – Second Monday of January. Celebrated nationwide, with ceremonies for young adults. Daily travel isn’t heavily disrupted, but you’ll see crowds around civic buildings and shrines, especially in cities.

Golden Week – 29 April to 5 May. This is the biggest travel period in Japan. Several public holidays fall back-to-back, and the entire country seems to move at once. Trains, flights, and hotels book out early, popular sights are crowded, and prices are often higher. Traveling during Golden Week is doable, but planning ahead is essential.

Marine Day – Third Monday of July. A summer holiday marking the sea. Coastal areas and beach destinations get busy, but cities are mostly unaffected.

Mountain Day – 11 August. A newer holiday that encourages time outdoors. Domestic travel increases, particularly to rural and alpine regions.

Obon Holiday Period – Mid-August (dates vary by region). Not a single public holiday, but one of the busiest travel periods of the year. Families travel home, trains fill quickly, and accommodation in regional areas can be hard to secure.

Respect for the Aged Day – Third Monday of September. A quieter holiday with minimal impact on travel, though some attractions may be busier with local visitors.

Autumn Equinox – Around 22–23 September. A national holiday that can create long weekends. Expect moderate increases in domestic travel.

Passport and Visa Requirements

Travelers from many countries, including U.S. passport holders, can enter Japan visa-free for up to 90 days for tourism. The most up to date visa information can be found here. We recommend checking if you need a tourist visa to enter Japan.

Your passport must be valid for the entire duration of your stay (Japan doesn’t require six months’ validity beyond departure, but airlines may have their own rules). On arrival, visitors are typically fingerprinted and photographed as part of standard immigration procedures.

If you plan to stay longer than 90 days, or your visit involves work, study, or residency, a visa must be arranged before travel through a Japanese embassy or consulate. Requirements can change, so it’s always smart to double-check the latest entry rules with your local Japanese embassy shortly before departure.

We recommend keeping your passport handy; hotels are legally required to register foreign guests, so most do ask to see your passport at check-in. A quick photo on your phone usually isn’t enough – keep the physical passport accessible.

Japan also technically requires foreign visitors to carry their passport at all times. Random checks are rare, but it does happen, especially in cities.

And remember that it is illegal to bring meat products including sausages, bacon and ham to Japan without permission from the Japanese Animal Quarantine Service. Penalties include a heavy fine and prison sentence.

You will be required to fill in a customs form when entering Japan which you can do online here before your trip and speed up border formalities.

Health & Safety

Japan is one of the safest countries in the world, and it’s normal to see women walking alone at night, commuting solo, or dining by themselves. Violent crime is very rare, streets are well lit, and public transport is secure at all hours.

Japan takes rules seriously. That extends to public behavior, which creates a strong sense of predictability and safety, especially if you’re traveling alone.

Japan’s big cities stay awake late, and it’s very safe to wander alone as a woman in Japan at night. Streets in Tokyo and Osaka remain busy well into the night, convenience stores stay open around the clock, and illuminated shop signs give the impression that everything runs nonstop. Public transport usually stops running around midnight.

Harassment is uncommon, but like anywhere, trust your instincts and remove yourself from situations that feel off. If something does happen, police are approachable and professional, though English levels can vary outside major cities. Unwanted attention like unwanted staring, verbal comments, and even men groping women on trains, is being reported as on the rise.

Healthwise, Japan is very straightforward. Tap water is safe to drink nationwide, food hygiene standards are high, and medical care is excellent – though it can be expensive, so comprehensive travel insurance is strongly recommended.

Wear a mask if you’re sick: If you have a cold, cough, sore throat, or even just feel a bit off, people expect you to mask up in public spaces like trains, shops, and restaurants. It’s a way of saying, “I respect the people around me.” Masks are sold everywhere, in convenience stores, pharmacies, vending machines, and they’re cheap, comfortable, and widely used.

Get that coverage: We never leave the house without purchasing extensive medical and travel insurance coverage and this is why we make it mandatory to join our tours. You should make sure that you have adequate medical insurance to cover any unforeseen medical expenses.

Unexpected accidents do happen, and if you needed to be evacuated back home with an injury, the medical bill could bankrupt you.

The best travel insurance will differ for each traveler, depending on the nature, style, and length of your trip, so we recommend using an aggregator and comparison tool such as Travel Insurance Masters to find the right one for you depending on what coverage you want, age, location, trip, etc.

Bring all the medication you’ll need: Pharmacies are well stocked in Japan, but it is strongly recommended to bring any prescription medication you may need and enough of it to last you the entire trip.

IMPORTANT: Some medications that are common elsewhere are restricted or banned in Japan, including certain ADHD meds and strong painkillers. Make sure any prescription medication comes in its original pharmacy packaging, and with the corresponding doctor note and prescription to avoid issues at the border. It is your responsibility to check that whatever medication you bring can indeed be taken into Japan. What may be legal in your country, or even sold over the counter, could be a controlled substance elsewhere. You should always check before the trip with the corresponding Japanese body.

No special vaccinations are required, beyond the recommended routine travel immunisations (CDC website here).

Tattoos in Japan have historically been associated with organised crime, and that perception hasn’t fully disappeared. The biggest place this comes up is at onsens (hot springs), public baths, pools, gyms, and some traditional accommodations. Many of these spaces restrict visible tattoos, regardless of size or meaning. Signage is usually clear, and staff will let you know if you need to cover up.

Some places are becoming more flexible, especially in tourist areas. You may see “tattoo-friendly” signs, or be allowed entry if tattoos are covered with patches or clothing. But it’s worthwhile carrying a lightweight cover, bandage, or rash guard is an easy workaround if you’re unsure.

Outside of baths and gyms, tattoos generally aren’t an issue. On the street, in shops, or at restaurants, no one will comment. Still, modest coverage in quieter or more traditional areas is often appreciated.

Earthquake safety: Japan does sit on the Pacific Ring of Fire, which means earthquakes are part of life here. Buildings are designed with this in mind, and emergency systems are clear and well practiced. Minor tremors are common and usually nothing to worry about. If something larger occurs, follow local instructions – signage and announcements are clear, and people around you will know exactly what to do.

Heat is the most common challenge for travelers, particularly in summer. Humidity can be intense, and heat exhaustion should be taken seriously. Vending machines everywhere sell water and electrolyte drinks like Pocari Sweat and Aquarius – grab them often, even if you don’t feel thirsty yet. I like to bring these hydrating tablets from Nuun with me.

Pace yourself during the middle of the day if you’re traveling in summer, and plan indoor breaks around museums, cafés, and shops. Air-conditioning is everywhere, and locals are quick to take breaks indoors. Lightweight clothing, a hat, and sunscreen make a noticeable difference, and many locals carry small towels to mop sweat.

Sun protection in Japan is taken seriously, and you’ll notice it almost immediately. On bright days, it’s common to see people walking with umbrellas even when the sky is clear – they’re being used as parasols, not rain cover. You’ll also spot long driving gloves, wide-brim visors, face coverings, and lightweight arm sleeves, worn by men and women alike. This isn’t about fashion or modesty, it’s about avoiding sun exposure altogether.

Japan treats UV protection as everyday health care, and preventing sunburn, pigmentation, and long-term skin damage is considered routine. You’ll see sunscreen bottles marked with a PA rating alongside SPF. This indicates protection against UVA rays (the ones linked to skin ageing). More “+” symbols mean higher protection, with PA++++ offering the strongest level.

In case of an emergency in Japan: Dial 110 for the police, and 119 for ambulance or fire services. Both numbers are available 24/7 across the country and can be called from any mobile or landline. Calls are free of charge, even if your phone has no credit or active SIM card.

Travel essentials for Japan

In this section we will look at a range of other things to consider when traveling to Japan as a solo female traveler.

Money and Currency

Japan uses the Japanese Yen (¥), and while the country feels futuristic in many ways, cash still plays a big role. Smaller restaurants, local cafés, temples, shrines, and rural shops often accept cash only. It’s normal to carry cash daily, and it’s safe to do so – petty theft is rare.

When you pay, don’t be surprised if your change is returned carefully on a small tray rather than placed directly into your hand. This is considered polite, and returning the tray rather than grabbing the money is a small gesture that’s noticed.

Tipping in Japan works very differently from what many travelers expect. Tipping is not customary and can actually cause confusion or embarrassment. Service is considered part of the job, not something that needs to be rewarded separately.

In restaurants, taxis, hotels, and shops, the price you see is the price you pay. If you try to leave extra money, staff will usually return it, sometimes chasing you down the street to do so (yes, it happened to us).

If you want to express appreciation, a sincere thank you goes much further than money. In situations where a specialist service is involved, appreciation is usually shown through words, a small gift from home, or a thoughtful note rather than cash.

Tour guides are used to foreigners and are increasingly accepting of tips, despite being very well compensated for their job. However, instead of handing rolled or folded notes (which you wouldn’t do to pay for anything either), place the tip in an envelope and give it with both hands. Or better yet, bring a gift from home and remember to wrap it well and with care.

ATMs that reliably accept foreign cards are found at convenience stores and Japan Post Offices. These are everywhere and easy to spot. Coins are used frequently, so don’t be surprised if your wallet gets heavy quickly.

Credit and Debit Cards: Cards are widely accepted in hotels, department stores, larger restaurants, and transport hubs, especially in big cities. Visa and Mastercard are the most reliable. American Express is accepted in some places, but not all. Don’t assume every café or shop will take cards – always have cash as backup.

Don’t bargain: Prices are fixed, tax is included, and bargaining isn’t a thing, even in markets or small independent stores. Prices are set fairly and consistently, and trying to negotiate can make staff uncomfortable rather than save you money. If something feels expensive, the expected response is simply not to buy it.

Wi-Fi and Mobile Data

Staying connected in Japan is easy, but you need to know how to navigate your connection.

Free Wi-Fi exists, but it’s not always seamless or consistent, and public networks in Japan often require registration, QR scans, or repeated log-ins, which can be frustrating when you’re on the move. Hotels almost always offer reliable Wi-Fi, and you’ll find it in cafés, major train stations, airports, and some long-distance trains, but it can drop out without warning, especially once you leave city centres.

The most reliable option besides roaming is pocket Wi-Fi or a local SIM/eSIM like Holafly (use the 5% discount code: SOLOFEMALETRAVELERS) or Airalo. Pocket Wi-Fi devices are popular in Japan because they’re fast, stable, and allow multiple devices to connect at once. But you may find an eSIM is better, because you’ll be relying on your phone a lot, and Japan has excellent mobile coverage.

Google Maps is essential for train transfers, platform numbers, and exit gates. Translation apps such as Google Translate will help with menus and signage since English isn’t commonly spoken. But beware that translations often don’t make sense or are comical because the Japanese language uses a lot of context that the app lacks. In all cases, having reliable connectivity removes a lot of friction.

The easiest places to get a SIM are international airports (Narita, Haneda, Kansai, etc.), where counters are clearly marked and staff are used to helping travelers. You can also pre-order online and pick up at the airport, which saves time and avoids language barriers. Some electronics stores in cities sell SIMs, but airport pickup is usually smoother.

Most Japanese SIMs are data-only. This is normal. You won’t get a local phone number, but apps like WhatsApp, FaceTime, and LINE work perfectly.

- Sakura Mobile – Very popular with international visitors. English support, clear setup instructions, good coverage, and airport pickup options.

- Mobal – Easy to use, good for longer stays, and known for clear pricing with no surprises.

- IIJmio – Often cheaper and widely sold at airports, though setup can be slightly less intuitive.

Power Plugs and Charging

Japan uses Type A and B plugs (the same shape as North America) and runs on 100 volts, which is lower than many countries. Most modern electronics handle this fine. Charging points are common in hotels and some cafés, but less so on trains. Many Japanese outlets do not have a grounding hole, even if they accept a Type B plug.

Cultural Etiquette in Japan

Japan is polite on the surface, and you are likely never going to know when you have offended someone or done something you shouldn’t.

Most visitors don’t offend anyone outright, but small misunderstandings can quietly create discomfort and knowing a few cultural cues goes a long way.

What most travelers feel is that they are offending, but don’t know why or how, since Japanese people will never point it out to you. Many rules are clear, but others are assumed and understood by the locals, yet not obvious to visitors.

Moreover, Westerners may do what is not only common but even celebrated in their own countries, yet offensive in Japan, for example, being direct, offering feedback or sharing criticism is viewed as embarrassing in Japan while it is the norm in some cultures.

In general, individualism is frowned upon in favor of collective harmony, so being considerate is taken to the extreme and prioritised. Take up less space, be modest, don’t touch things or people around you, be quiet and mindful of others at all times and you are likely to be fine.

- Photography is not always allowed in temples, shrines, or shops, look for signs before taking photos, and always ask permission. If you plan to take photos of another person, including Geishas, ask before, Japan has strict privacy laws. Never take photos of children.

- Quiet is a form of respect. On trains and buses, conversations are soft or silent. Phone calls are avoided entirely. It’s not about rules, it’s about not imposing yourself on shared space. If you follow the lead of those around you, you’ll notice how calm public transport feels.

- Queuing is sacred. People line up neatly for trains, escalators, lifts, and even vending machines. Jumping the queue or hovering too close can feel intrusive. When in doubt, look for floor markings – Japan tells you where to stand if you pay attention.

- Taking up space in an escalator. On escalators is where Japanese etiquette is most clear. There is a standing side and a walking side. If you want to stand and wait, you should stand and take up the least amount of space, so others who prefer to walk can pass you by. If you have luggage, this should be in front of behind you, never next to you.

- Shoes matter more than you expect. You’ll be asked to remove shoes in some restaurants, temples, traditional accommodation, and private homes. Slippers are often provided – but they’re for indoor use only. To enter the toilet, there are often pairs of slippers to change into to enter the bathroom. One classic mistake is wearing toilet slippers back into the main space. Locals will never scold you, but they will notice.

- Taxi doors open automatically. Taxis in Japan are also technologically advanced and doors will open when the car stops. This is no fancy high-tech mechanism but a simple mechanical lever. Just be patient and don’t try to open the door yourself.

- Hands off, voices down. Public displays of affection are frowned upon and locals never kiss or hug. Hugging, loud laughter, or expressive gestures can feel out of place in quiet settings. Even a pat on the back will be seen as intrusive. Public arguments are a huge no-no. It’s not coldness – it’s restraint.

- Cash, cards, and objects are handled deliberately. Money is placed on trays, not handed directly. Receipts are given carefully. Items are often passed with two hands. These small gestures signal care, not formality.

- Yukata bathrobes are worn everywhere. Most ryokans and onsen hotels and resorts will provide yukata, or lightweight robes, to be used indoors throughout the building, and to the onsen. I still remember being at a 5* international chain hotel and going down to dinner only to find everyone but me in the traditional clothing.

- Don’t eat while walking, or eat in public spaces like stairs. Street food exists, but it’s usually eaten standing beside the stall, not while moving. Walking and eating at the same time can be seen as careless or messy, like “lacking in civility”. Eating or drinking in public transportation is a big no, although this is changing a bit and you may see younger generations discretely sipping a coffee through a straw. On the other hand, it is fine and even a part of the experience, to eat bento boxed food in the Shinkansen bullet train, just like we will do on our tour when we will prepare our own bento boxes and then eat them at the Shinkansen on our way to the countryside.

- Tattoos aren’t always casual. Tattoos still carry associations with organised crime in some settings. Many onsen, pools, and gyms restrict visible tattoos. Some allow them if covered – always check signage before entering.

- Avoid blowing your nose in public. It’s more polite to sniff discreetly or excuse yourself to a restroom. This surprises many visitors, but it’s a deeply ingrained social norm. Reusable cloth handkerchiefs are also seen as unhygienic.

- Wear a mask if you’re sick: If you have a cold, cough, sore throat, or even just feel a bit off, people expect you to mask up in public spaces like trains, shops, and restaurants. It’s seen as a quiet way of saying, “I respect the people around me.”

- Politeness isn’t enthusiasm. Smiles, bows, and apologies don’t always mean agreement or happiness. They often signal smoothness; keeping interactions comfortable rather than confrontational.

- Lost items actually come back. Japan’s lost-and-found culture is real. If you lose something, report it. People return wallets, phones, and bags with astonishing consistency.

- The biggest rule: don’t stand out on purpose. Japan values harmony over individuality in shared spaces. You don’t need to blend in perfectly, just aim to take up less space than you think you should. That mindset alone earns quiet respect.

- Using chopsticks: Avoid sticking chopsticks upright in rice or passing food chopstick-to-chopstick, both are linked to funeral rituals. When not in use, rest them on the holder or across your bowl.

- Being late: Punctuality matters. Arriving late, even by a few minutes, can feel disrespectful, especially for trains, reservations, or group meet-ups, and reservations may be cancelled due to late arrival. If you’re running behind, a quick apology goes a long way.

- Bowing is a common way to greet, thank, apologise, or show respect in Japan, but visitors aren’t expected to master it. A small, gentle nod of the head is more than enough in most situations. You’ll see deeper bows used in formal settings, but those are part of professional or ceremonial life rather than everyday interactions.

The key thing to know is that bowing isn’t about precision – it’s about intention. Returning a bow, even awkwardly, is always appreciated. If you’re unsure, follow the other person’s lead. A brief bow paired with a smile communicates respect far better than getting the angle exactly right. Bowing is so common that even the deer in Nara do it.

- Don’t automatically expect locals to speak English. You’re in their country, and daily life runs in Japanese. This mindset matters, and even a small attempt, like a greeting, a thank you, a polite excuse, shows respect and awareness, and will be met with genuine warmth. No one expects fluency, but what is noticed is effort. Assuming English will be spoken, or expressing frustration when it isn’t, can come across as entitled and will not be appreciated.

- Onsen/sento rules (and tattoos). Wash thoroughly before getting in at the small cubicles provided, body and hair. No swimwear in most baths, you need to be completely naked unless stated otherwise. Tie your hair up to avoid it touching the water. Tattoos can be restricted at some hot springs – check ahead or bring a cover patch if permitted. You will be handed two towels, a small and a large one. Use the small towel to dry off your forehead or keep your head warm if it’s cold and the onsen is outside, but never let it touch the water. The larger towel is to be used to dry off after soaking. Don’t run or talk loudly in onsens, they are meant to be quiet and relaxing environments for everyone. Important: Onsens are natural hot springs so the water can be very hot, get out if you feel dizzy and check in with your doctor before trying them out.

- Walking dead-center through shrine gates/paths. At many shrines, the middle line is treated as a special passage. Step slightly to the side, and treat it like a place of worship – not a photo set.

- Strong perfume. Crowded spaces are common, so strong scents can feel inconsiderate to others and will not be allowed at high end sushi places where the food is meant to be enjoyed with your five senses.

- Slurping noodles is acceptable, but not burping.

- Gift giving is sacred. Gifts are thoughtfully wrapped and presented and their appearance is often more important than what is inside. The Japanese even have gift wrapping techniques and knot styles such as Furoshiki which uses a square cloth to wrap sustainably. Gifts given without a beautiful presentation are seen as disrespectful.

- Pointing with a finger is rude. Instead, gesture with an open hand.

- Take your trash with you. There are practically no public bins in Japan so you are expected to take your trash with you in a small resealable bag. Littering is seen as extremely rude as cleanliness is a sign of respect. Pro tip: 711 and Family Mart have small bins.

Prohibited goods

There are some goods and items that are illegal to take, possess or import in Japan:

- Import and export of ivory is prohibited by law.

- Do not touch or remove coral, fish or other sea life.

- Never pick flowers, tree branches or take wild grass as a souvenir. This includes sakura flowers.

- Do not harm wild animals.

- Any sword, even a fake replica, whose length is above 15 centimeters is strictly prohibited to either be possessed or carried in Japan.

The legal drinking and smoking age in Japan is 20. Drugs are illegal and punishment for possession is very strict, including arrest and deportation.

Basic Japanese Words to Know

As you now know, English isn’t widely spoken in everyday situations in Japan, even in business settings, and translation apps are not the best, so small language gaps are part of the experience.

You don’t need fluency, but knowing a handful of polite, practical words makes daily interactions smoother and more comfortable.

These basics help with shops, restaurants, trains, and simple requests, and just as importantly, they show respect and effort. You can practice your Japanese before traveling with language learning apps like Mondly here.

- Hello / Good afternoon – こんにちは Konnichiwa (kon-nee-chee-wah)

- Good morning – おはようございますOhayō gozaimasu (oh-ha-yoh go-zai-mahss)

- Good evening – こんばんは Konbanwa (kon-bahn-wah)

- Thank you – ありがとうございます Arigatō gozaimasu (ah-ree-gah-toh go-zai-mahss)

- Thank you (casual) – ありがとう Arigatō (ah-ree-gah-toh)

- Excuse me / Sorry / Get attention – すみません Sumimasen (soo-mee-mah-sen)

- Please – お願いします Onegaishimasu

- Yes / I understand – はい Hai (hi)

- No – だいじょうぶ Daijobu

- This / That – これ / それ Kore / Sore (koh-reh / soh-reh)

- How much is this? – これはいくらですか?Kore wa ikura desu ka? (koh-reh wah ee-koo-rah dess kah)

- Please help me – 助けてください Tasukete kudasai (tah-soo-keh-teh koo-dah-sigh)

- Where is…? – ~はどこですか? …wa doko desu ka? (wah doh-koh dess kah)

Besides the useful ones, Japanese has many unique words that don’t have a translation in other languages.

Kawaii refers to the entire culture of cuteness, while Tsundoku means buying books to pile them unread. Ikigai is your reason for being, Wabi-sabi means beauty in imperfection, Kuchi-sabishii is the feeling of an empty mouth, wanting to snack or chew on something and Natsukashii is a nostalgic feeling of fondness for something from the past. And there are many more.

Local Cuisine

Japanese cuisine is UNESCO listed and globally celebrated. The Michelin guide includes 351 restaurants with at least 1 star. Tokyo is home to 12 three Michelin star restaurants.

Japanese gastronomy is built around balance, seasonality, and respect for ingredients. Meals can be either refined or casual, but even the simplest dish is usually prepared with care. Eating well in Japan doesn’t require a special occasion, it’s woven into everyday life.

Food culture here goes far beyond a list of famous dishes. What people eat changes with the seasons, the region, and even the time of day. There’s a clear rhythm to meals: quick, nourishing comfort food designed for busy city life sits comfortably alongside slow, thoughtful multi-course dining rooted in tradition.

Presentation matters a lot, but never loudly. It’s about colour, proportion, and letting ingredients speak for themselves. Meals aren’t rushed or performative; they’re practical, intentional, and part of daily routine rather than a spectacle.

That approach comes from history as much as taste. Japan’s geography – an island nation with long coastlines, mountainous interiors, and limited farmland – shaped a cuisine centred on seafood, rice, vegetables, and preservation techniques like fermenting, pickling, and drying.

Buddhist influence reduced meat consumption for centuries, while trade with China and Korea introduced noodles, soy sauce, tofu, and tea. Later contact with the West added elements like breading, curry, and deep-frying, which Japan quietly adapted into its own style. Instead of replacing what came before, Japanese cuisine absorbed new ideas carefully, refining them until they felt native. The result is food that feels both ancient and everyday.

Sushi & Sashimi

Sushi and sashimi are often mentioned together, but they’re not the same thing, and understanding the difference makes ordering far less intimidating.

Sashimi is the simplest form: thinly sliced raw fish served on its own, without rice. The focus here is entirely on freshness, texture, and knife skill. There’s nowhere to hide, which is why sashimi is usually excellent in Japan, even at modest restaurants. It’s often eaten with a light dip of soy sauce and a touch of wasabi, but restraint matters. Overpowering the fish misses the point.

Sushi, on the other hand, pairs fish or seafood with vinegared rice. The most common style you’ll see is nigiri – a small mound of rice topped with fish – but sushi also includes rolls, pressed sushi, and hand rolls. Good sushi is about balance: the temperature of the rice, the seasoning, the cut of the fish, and how it all comes together in one bite.

Adding too much soy sauce to either of the two will mask the flavor of the high quality fish and offend the chef. Eating either with your hands is acceptable, especially at sushi bars.

Where to eat: Both sushi and sashimi are at their best in Tokyo, where access to top-quality seafood and generations of craftsmanship come together, from casual counters to refined sushi bars.

Ramen

Ramen is everyday food in Japan, not a novelty dish, and part of the fun is how seriously it’s taken. At its core, ramen is wheat noodles served in a carefully built broth, but that simple description hides an enormous range of styles, textures, and regional preferences.

The broth is where most of the variation happens. Shoyu (soy sauce) ramen tends to be lighter and aromatic, miso ramen is richer and slightly sweet, shio (salt-based) ramen is clean and delicate, and tonkotsu ramen uses pork bones simmered for hours to create a creamy, full-bodied soup. Noodles vary too – thin and straight, thick and curly – chosen to match the broth.

Toppings are usually simple: sliced pork (chashu), green onions, bamboo shoots, seaweed, and a soft-boiled egg. Ramen shops often specialise in one style and do it extremely well. Menus can be short, and many places use vending machines at the entrance where you buy a ticket before sitting down. This isn’t impersonal – it keeps things efficient and focused on the food.

Where to eat: Ramen is everywhere, but regional styles shine — Fukuoka is famous for rich tonkotsu, Sapporo for hearty miso ramen, and Tokyo for soy-based broths with layered depth.

Slurping is completely normal and even encouraged. It helps cool the noodles and shows appreciation.

Other Delicious Japanese Foods

Japanese cuisine is filled with yum foods that are traditionally local and not found anywhere else.

Tempura: Seafood or vegetables lightly battered and fried until crisp, without heaviness. Good tempura feels clean and delicate, not greasy.

Where to eat: Traditionally associated with Tokyo, where it’s often treated as a craft and served in specialist restaurants.

Okonomiyaki: A savoury pancake made with cabbage, batter, and various toppings, cooked on a hot plate and finished with sauce.

Where to eat: A proud specialty of Osaka and Hiroshima, each with its own distinct style.

Yakitori: Grilled chicken skewers, seasoned simply or brushed with sauce. Often eaten casually with a drink after work.

Where to eat: Especially popular in Tokyo, near train stations and in izakaya districts, though common nationwide.

Tonkatsu & Katsu Curry: Breaded pork cutlet served alone, in sandwiches, or paired with rich Japanese curry. Filling, comforting, and widely loved.

Where to eat: Eaten across Japan, with excellent versions in Tokyo and Osaka.

Donburi (Rice Bowls): Rice topped with beef, chicken, egg, or fried cutlets. Simple, satisfying, and fast.

Where to eat: Found everywhere, especially in busy city areas and near stations, particularly in Tokyo.

Udon & Soba: Thick wheat noodles (udon) or thin buckwheat noodles (soba), served hot or cold depending on the season.

Where to eat: Udon is strongly linked to Shikoku, while soba is traditionally associated with Nagano.

Takoyaki: Bite-sized batter balls filled with octopus, topped with sauce and bonito flakes. Hot, messy, and addictive.

Where to eat: A street-food icon from Osaka, best eaten fresh from market or festival stalls.

Japanese Curry: Mild, thick curry served over rice or noodles, often with vegetables or a fried cutlet.

Where to eat: Popular nationwide, especially in Tokyo and Osaka as everyday comfort food.

Onigiri (Rice Balls): Hand-shaped rice filled with salmon, pickled plum, or tuna mayo, wrapped in seaweed.

Where to eat: Everywhere – convenience stores, train stations, and local shops across Japan.

Takikomi Gohan: Rice cooked with vegetables, mushrooms, fish, or meat, often reflecting seasonal ingredients.

Where to eat: Common in rural regions and traditional eateries, especially in autumn.

Traditional Sweets (Mochi, Taiyaki, Dango): Chewy rice cakes, filled fish-shaped pastries, and skewered dumplings, often tied to seasons or festivals.

Where to eat: Found nationwide, with strong cultural ties to Kyoto and temple towns.

Miso soup: Made of miso in a dashi stock (dried baby sardines, dried kelp, thin shavings of fermented, dried, and smoked bonito or dried shiitake) with cubes of tofu and spring onion and usually served as part of a meal along with rice and side dishes.

Where to eat: Probably the most common dish found across the country.

Delicious Japanese Drinks & Drinking Culture

Drinking in Japan is social, but alcohol isn’t about excess or bravado; it’s about connection, pacing, and knowing your place in the group.

Much of Japan’s drinking culture happens in izakayas – casual bars serving small plates meant for sharing. They’re social spaces, not rowdy, and will feel less like a party and more like a shared pause in the day.

Here are some delicious Japanese drinks to try, and notes on the drinking culture, which is unique to Japan.

Sake (Nihonshu): What most people call “sake” is known locally as nihonshu, and it’s far more varied than you expect. Some are light and dry, others rich and slightly sweet, served chilled, room temperature, or gently warmed depending on the style and season.

Good sake isn’t meant to burn, it’s meant to complement food. You don’t need to know labels; asking for a local recommendation is normal.

Beer: Beer is the most common everyday drink, especially in social settings. It’s crisp, easy to drink, and usually ordered first. Draft beer (nama bīru) is everywhere, and convenience stores sell excellent canned options. Drinking a beer outside a shop or sitting casually on a curb isn’t unusual.

Shochu: Shochu is a distilled spirit made from barley, sweet potato, or rice. It’s typically lower in alcohol than whisky or vodka and often mixed with water or soda. It’s especially common in southern Japan.

Highballs & Chu-hai: Highballs (whisky with soda) and chu-hai (shochu mixed with soda and fruit flavours) are hugely popular. They’re light, refreshing, and easy to pace – a big reason they’re common at long dinners or after work.

Non-Alcoholic Options: Japan does non-alcoholic drinks exceptionally well. Matcha tea, iced teas, flavoured sodas, alcohol-free beer, and seasonal soft drinks are everywhere. Choosing not to drink is completely acceptable.

Drinking Etiquette:

- Don’t pour your own drink in group settings. Someone else usually does it for you, and you return the favour.

- Wait for a brief “cheers” (kanpai) before drinking with others.

- Pacing is normal. No one rushes you, and leaving early isn’t rude.

- Being visibly drunk in public is not appreciated. Moderation is respected.

Japanese Table Manners

Japanese table manners are about awareness, gratitude, and not drawing unnecessary attention to yourself. You don’t need to get everything right, but a few habits make a big difference.

Before eating, it’s customary to say “itadakimasu”, which loosely means I gratefully receive. It’s not religious or formal, just a quiet acknowledgment of the meal. It means you are grateful to everyone involved in putting the meal on the table. meaning, farmers, cooks, the people who prepared and served the food. At the end, “gochisōsama deshita” is a polite way to say thank you for the food.

Chopstick etiquette matters more than knife-and-fork precision. Avoid sticking chopsticks upright in rice, using them to point at someone or passing food directly from one set of chopsticks to another, as both are linked to funeral rituals. When you pause, rest chopsticks on the holder or across your bowl, not directly on the table. Use serving chopsticks to serve food, or the opposite end of your chopstick if there are none.

Slurping noodles is completely acceptable and even encouraged. It cools the food and signals enjoyment. Chewing quietly, however, is expected, and talking with a full mouth is frowned upon.

It’s polite to lift bowls closer to your mouth when eating rice or soup rather than leaning down toward the table. Soup is usually sipped directly from the bowl, with chopsticks used to catch solid ingredients.

Sharing dishes is common, but use the serving utensils if provided, or the clean end of your chopsticks. Don’t spear food or gesture with chopsticks – they’re treated with quiet respect.

Finishing your meal is appreciated. Leaving large amounts of food can feel wasteful, so smaller orders are better if you’re unsure.

Books about or set in Japan

There are a couple of books worth reading before your trip:

Memoirs of a Geisha: A historical novel set in Kyoto before and after World War II, following the life of a young girl trained as a geisha. While fictional and written by a Western author, it offers a vivid sense of atmosphere, tradition, and the rigid social structures of the time – best read as storytelling rather than documentary. It’s a great book, but it does sustain the myth of Geisha as high-paid prostitutes, which is not the case. They are performers and entertainers.

Lost Japan: A thoughtful look at traditional Japanese culture and how it has changed over time. Part travel writing, part cultural critique, and very observant.

The Japanese Mind: A practical introduction to key Japanese concepts and values, explained simply. Helpful for understanding everyday behaviour without stereotypes.

Tokyo Vice: A fast-paced memoir about crime reporting in Tokyo. Gritty and modern, it shows a side of the city visitors rarely see.

Norwegian Wood: A quiet, emotional novel set in Tokyo in the 1960s by Nobel Laureate Haruki Murakami. It captures youth, loneliness, and everyday life more than landmarks.

Kitchen: Short, gentle, and deeply Japanese in tone. A story about grief, food, and human connection in modern urban Japan.

The Tale of Genji: Written over 1,000 years ago, this is often considered the world’s first novel. It offers a window into court life during Japan’s Heian period.

Hokkaido Highway Blues: Funny, observant, and relatable. A travel memoir about chasing cherry blossom season across Japan by a foreign writer.

Shōgun: A sweeping historical epic 6-book saga in feudal Japan. Dramatic and immersive, though fictionalised, it sparked Western fascination with samurai-era Japan.

Japanese movies and movies about or set in Japan

Here is a list of movies about or set in Japan, which you can watch before your trip, or download for the plane on the long flight over:

Spirited Away (2001): A modern animated masterpiece by Studio Ghibli that follows a young girl navigating a magical spirit world rich with folklore and emotion. It won global awards and remains one of the most celebrated films to come out of Japan.

On This Corner of the World (2016): A gentle but deeply affecting animated film set in Hiroshima before and during World War II. It follows an ordinary young woman navigating love, loss, and daily life as history unfolds around her, offering a quiet, human view of wartime Japan without spectacle or sentimentality.

Perfect Days (2023): A calm, contemplative portrait of everyday life in Tokyo, following a man who finds meaning in routine, work, and small pleasures. The film captures modern Japan at a slow pace, focusing on presence, simplicity, and the beauty of ordinary moments rather than big plot points.

Seven Samurai (1954): Akira Kurosawa’s epic about villagers hiring samurai to defend them from bandits. It’s a classic of world cinema and a gripping look at loyalty, strategy, and life in feudal Japan.

Rashomon (1950): Another Kurosawa gem that examines truth and perception through conflicting eyewitness accounts of a crime in ancient Japan. A powerful introduction to Japanese storytelling and film style.

Tokyo Story (1953): A quietly moving drama about family, aging, and modern life, set against the post-war pace of Tokyo. It’s less flashy than an action film but deeply human.

Departures (2008): This Oscar-winning Japanese film follows a cellist who returns to his hometown and discovers a profession preparing the dead for funerals. Beautiful, thoughtful, and very Japanese in its blend of humour and emotion.

Jiro Dreams of Sushi (2011): A documentary that immerses you in Tokyo’s sushi culture through the life of legendary sushi master Jiro Ono and his quest for culinary perfection.

Lost in Translation (2003): Set in Tokyo, this English-language film captures the humorous and poignant feelings of culture shock and connection while exploring the city’s neon heart. Featuring Scarlett Johansson and Bill Murray.

Godzilla Minus One (2023): A recent entry in the Godzilla franchise that roots its monster spectacle in post-war Japan, exploring themes of loss and recovery.

Memoirs of a Geisha (2005): An international film based on a novel set in Kyoto’s hanamachi districts, offering a fictional but vivid glimpse into the world of geisha. It’s a great story, but it does sustain the myth of Geisha as high-paid prostitutes, which is not the case. They are performers and entertainers.

Mr. Baseball (1992): A fun cross-cultural story about an American baseball player adapting to life on a Japanese team and learning the quirks of local customs and baseball culture.